4. Installation

40 PNEG-2381 2000 Series U-Trough Bin Sweep Auger Unload System (72' - 78')

Poly-Chain Alignment

NOTE: Proper alignment can increase the belt drive performance.

Introduction

Misalignment is one of the most common causes of premature belt failure. Depending on its severity,

misalignment can gradually reduce belt performance by increasing wear and fatigue. Or, it can destroy a

belt in a matter of hours or days.

While the forms of misalignment may be fairly well understood, accurate measurements and acceptable

limits must be determined if maintenance personnel are to take corrective action.

Types of Alignment

Basically, any degree of misalignment, angular or parallel, will decrease the normal service life of a

belt drive.

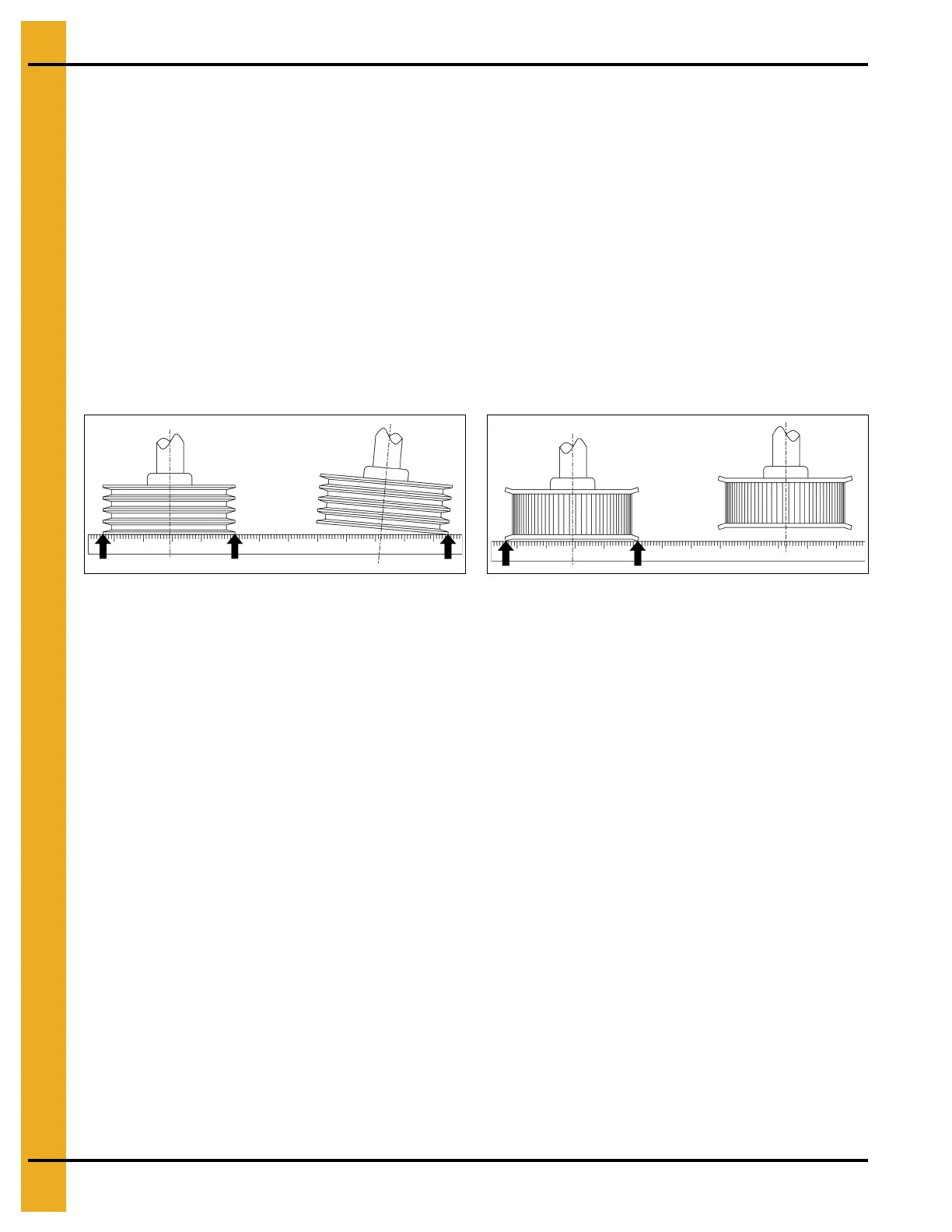

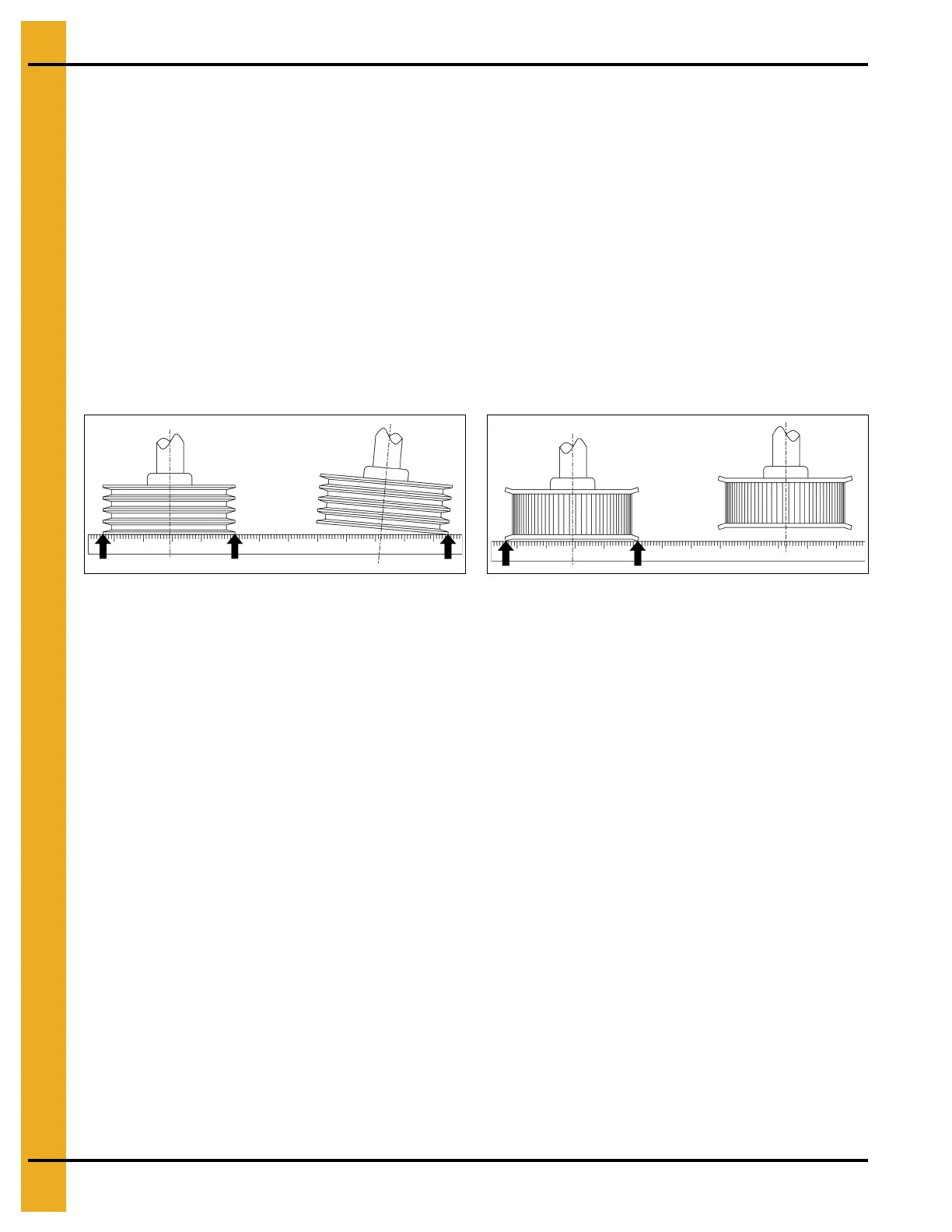

Figure 4BD Angular Misalignment Figure 4BE Parallel Misalignment

Angular misalignment results in accelerated belt/sheave wear and potential belt stability problems with

individual V-belts. A related problem, uneven belt and cord loading, results in unequal load sharing within

multiple belt drives, and can lead to premature failure. Joined V-belts can suffer tie band separation when

operating under misaligned conditions. Gates Corporation Power Transmission Product Application

engineers caution that angular misalignment has a severe effect on the performance of synchronous belt

drives.

Symptoms such as high belt tracking forces, uneven tooth/land wear, edge wear, high noise levels, and

potential tensile failure due to uneven cord loading are typical indicators of misalignment. Also, wide

synchronous belts are more sensitive to angular misalignment than narrow belts.

Parallel misalignment also results in accelerated belt/sheave wear and potential belt stability problems

with individual V-belts. Uneven belt and cord loading is not as significant a concern as with angular

misalignment. However, parallel misalignment is typically more of a concern with V-belts than with

synchronous belts. This is because V-belts run in fixed grooves and cannot free float between flanges, as

synchronous belts can, to a limited degree.

Parallel misalignment is generally not a critical concern with synchronous belt drives as long as the belt is

not trapped or pinched between opposite flanges, and as long as the belt tracks completely on both

sprockets.

Synchronous sprockets are designed with face widths greater than the belt widths to prevent problems

associated with tolerance accumulation, and to allow for a small amount (fractions of an inch) of mounting

offset.

As long as the width between opposite sprocket flanges exceeds the belt width, the belt will automatically

align itself properly as it seeks a comfortable operating position on both sprockets. It is normal for a

synchronous belt to lightly contact at least one of the sprocket flanges in the system while operating.

Synchronous belts rarely run in the middle of the sprockets without contacting at least one flange.

Loading...

Loading...