1-8 RPL Programming

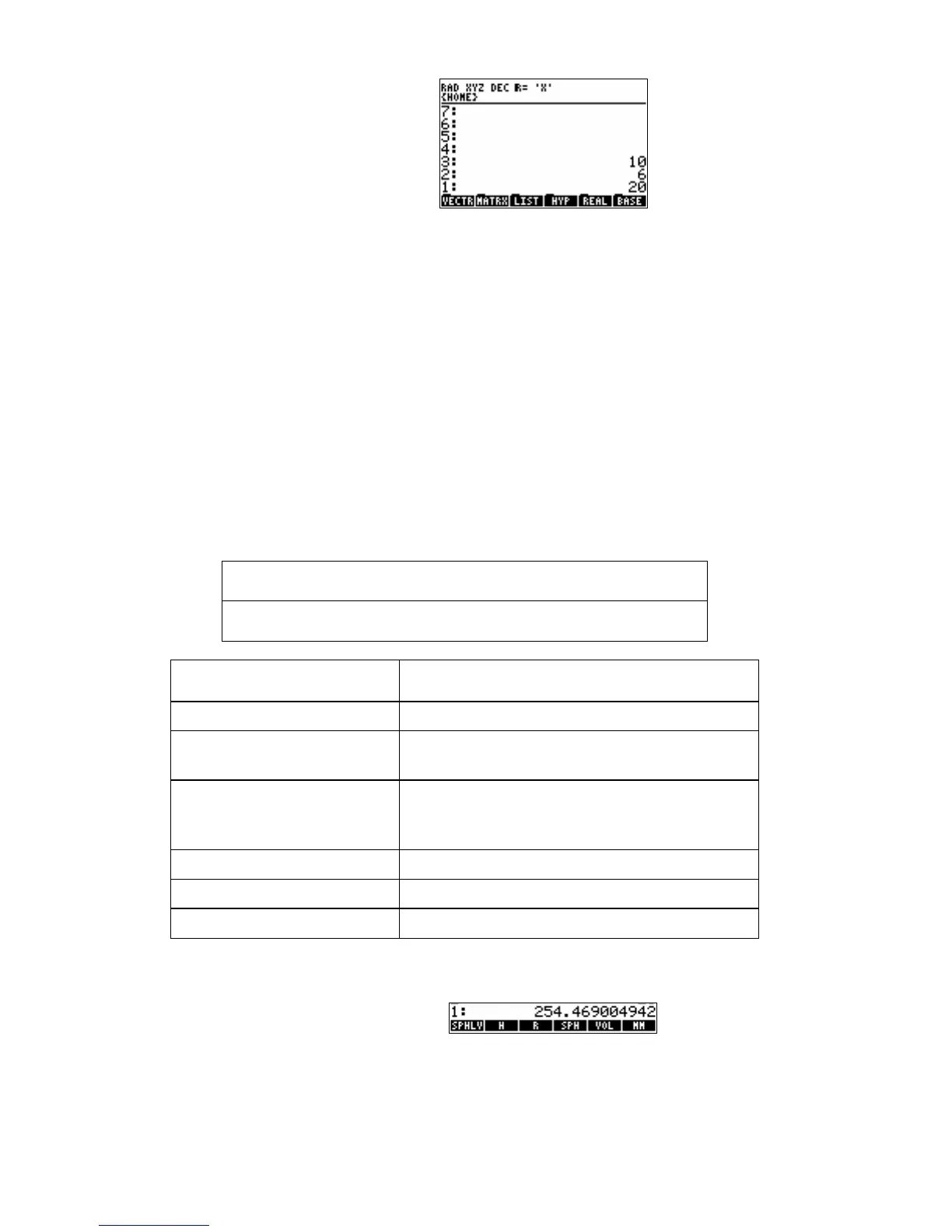

then

a creates local variable a = 20.

ab creates local variables a = 6 and b = 20.

abc crates local variables a = 10, b = 6, and c = 20.

The defining procedure then uses the local variables to do calculations.

Local variable structures have these advantages:

! The " command stores the values from the stack in the corresponding variables — you don't need to

explicitly execute STO.

! Local variables automatically disappear when the defining procedure for which they are created has

completed execution. Consequently, local variables don't appear in the VAR menu, and they occupy user

memory only during program execution.

! Local variables exist only within their defining procedure — different local variable structures can use the

same variable names without conflict.

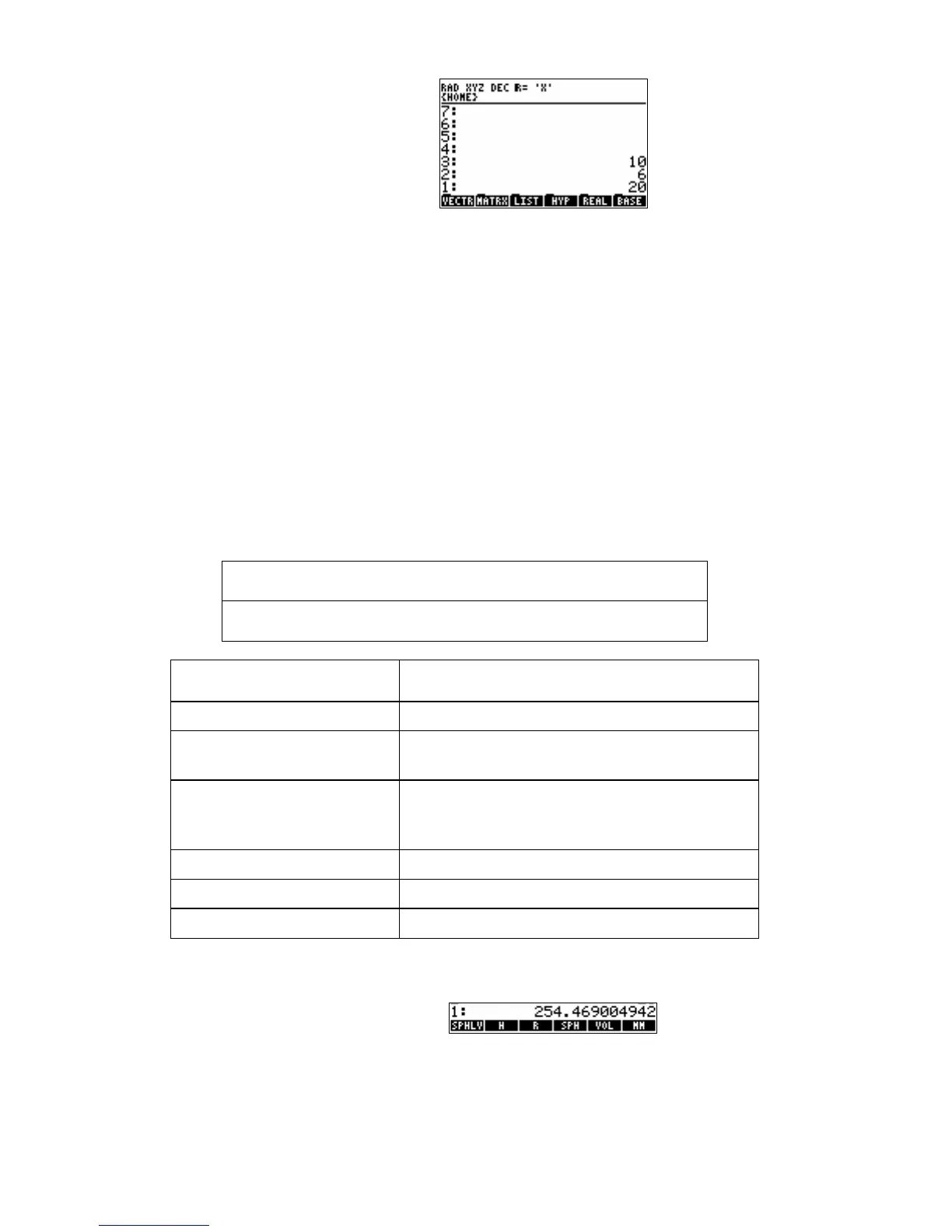

Example: The following program SPHLV calculates the volume of a spherical cap using local variables. The

defining procedure is an algebraic expression.

Level 2 Level 1 " Level 1

r h

"

volume

Program: Comments:

«

r h

Creates local variables r and h for the radius of the

sphere and height of the cap.

'1/3*œ*h^2*(3*r-h)'

Expresses the defining procedure. In this program,

the defining procedure for the local variable

structure is an algebraic expression.

NUM

Converts expression to a number.

»

OSPHLVK

Stores the program in variable SPHLV.

Now use SPHLV to calculate the volume of a spherical cap of radius r =10 and height h = 3. Enter the data on

the stack in the correct order, then execute the program.

10 `3

J%SPHLV%

Evaluating Local Names

Local names are evaluated differently from global names. When a global name is evaluated, the object stored in

the corresponding variable is itself evaluated. (You've seen how programs stored in global variables are

automatically evaluated when the name is evaluated.)

Loading...

Loading...